INSPIRATION

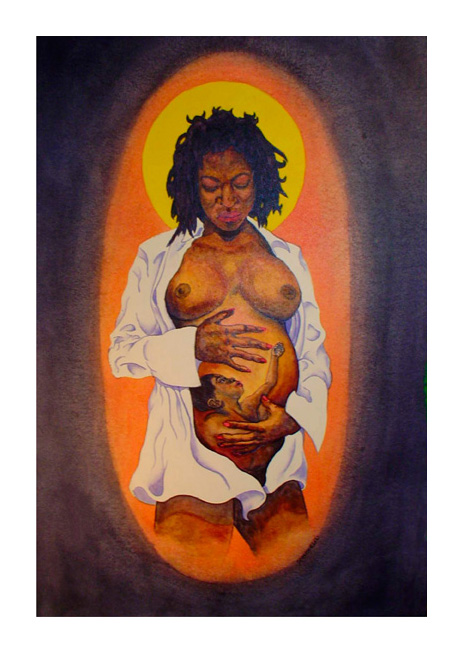

Although this image has flowered recently, the nights of reflection and debate that planted the seeds for its creation go back almost 20 years. Seeds that were planted during my second semester at seminary where I received my initial exposure to the writings of Dr. James Cone, the parent of Black Theology. That seed was then watered by the writings of Gustavo Gutierrez, the parent of Latin American Liberation Theology, and fertilized in the fruitful soil of ongoing theological debate and reflection.

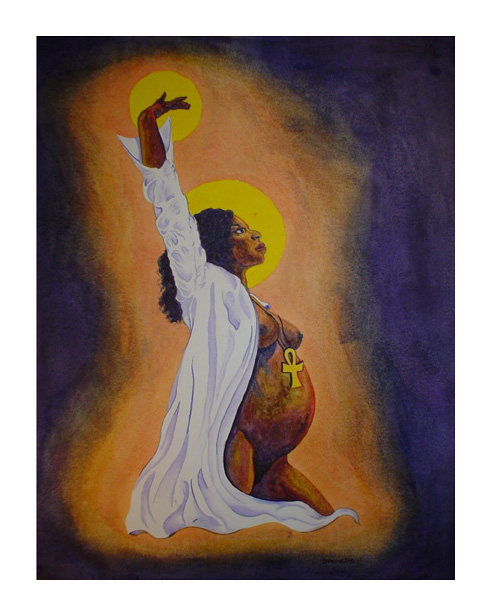

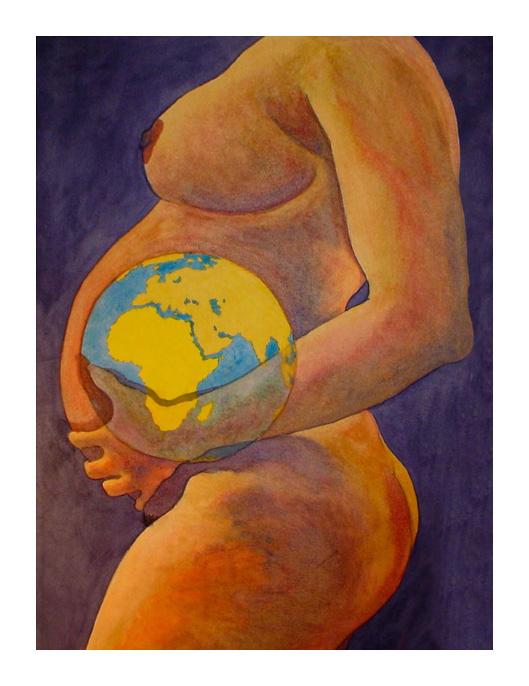

I find both ironic and appropriate that I have given birth to an image of Jesus so close to the season in which his birth is celebrated throughout the world. For some this birth means nothing – and for others everything. The most practical and pertinent questions have nothing to do with whether or not Jesus ever existed as an actual person, is he the son of god…and everything to do with his contemporary relevance in a world where his presence (real or otherwise) has made a lasting impression. There are so many differing voices and factions claiming possession of Jesus that it’s extremely difficult to discuss his relevance to the current state of affairs, until we ascertain “whose” Jesus we should be talking about? God of the Oppressed is a visual response to this question.

SYMBOLISM

Imagery

The nature of representational imagery necessitates the use of smaller, individual images (image begets image). The smaller individual images within the overall composition were carefully selected to support the overarching theme, “God of the Oppressed”. In the process of supporting this theme, I have placed the images together in ways that detail or elaborate upon certain aspects of the theme while simultaneously reinforcing or supporting the other images around it. In this way, their interdependence mirrors our own interdependence.

The Asian male with his hand raised in defiance counter-balances the outstretched arm of Hitler behind him. The handcuffed figure in the prison garb is directly connected to the silhouetted figure behind bars – yet both are directly linked to the police officer firing his gun as he holds the dangling head of yet another victim…we go on and on this way as we circle our way around the entire composition. My point with this effect was to remind us that despite all our futile attempts to deny our interdependence, each of us is connected to one another in myriad ways. The injustices we exercise upon another have an effect upon us, them, and the whole of humanity.

The Scriptural Texts

The figures carrying signs in the image’s lower left corner are central to its interpretation. Each of the figures holds a sign containing excerpts from key biblical texts. The young man in front stands before a sign which contains an excerpt from Luke 4.16-21 that reads: “When he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, he went to the synagogue on the sabbath day, as was his custom. He stood up to read, and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was given to him. He unrolled the scroll and found the place where it was written: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” And he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. The eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. Then he began to say to them, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.”

The gentleman walking behind the young man carries a sign with excerpts from Exodus 3.7-10 which states: Then the Lord said, “I have observed the misery of my people who are in Egypt; I have heard their cry on account of their taskmasters. Indeed, I know their sufferings, and I have come down to deliver them from the Egyptians, and to bring them up out of that land to a good and broad land, a land flowing with milk and honey, to the country of the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites. The cry of the Israelites has now come to me; I have also seen how the Egyptians oppress them. So come, I will send you to Pharaoh to bring my people, the Israelites, out of Egypt.”

The final text is carried by a woman wearing a hat who marches just behind the two gentlemen. Her message is excerpted from the famous “Magnificant” contained in Luke 1.46-55: And Mary said, “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior, for he has looked with favor on the lowliness of his servant. Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed; for the Mighty One has done great things for me, and holy is his name. His mercy is for those who fear him from generation to generation. He has shown strength with his arm; he has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts. He has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty. He has helped his servant Israel, in remembrance of his mercy, according to the promise he made to our ancestors, to Abraham and to his descendants forever.”

The central theme within each of these texts is the emphasis upon liberation from oppression, suffering and injustice. Not only liberation from, but more importantly solidarity with those whose lives are being affected by injustice. Solidarity from a divine intelligence that feels what they feel, hears their cries and provides comfort in the midst of unjust and often hostile circumstances. A divinity that not only identifies with us in our brokenness but also promises to take concrete action toward justice on our behalf. These actions are not solely focused upon comfort for the soul but are grounded in concrete historical reality. There is no “pie in the sky” or promise of future glory in the hereafter. These are the actions of a being who walks with us and works on our behalf within the context of our present reality. Freedom and justice are to be struggled for “now” because they are pertinent to our physical experience.

These texts present us with a divinity that is filled with compassion and actively concerned with justice. A god who not only takes sides but exercises a preferential option for those who are oppressed. This is a divinity who cannot be contained or co-opted by the establishment. A creator who loves us all, but is willing to not only take sides and become proactively involved with our efforts to balance the scales of justice. That is why these texts lie at the core of my personal theology and are intimately connected to every other aspect of this image.

Jesus

The image of Jesus serves as the central figure within this illustration. He is surrounded by a mandorla like shape which is also representative of the fish symbol that the early church appropriated to depict their faith and mission. I intentionally made sure that the figure not only breaks through the mandorla to touch the other figures but the tail portions of the mandorla also connect with the outer figures as well. This helps unify the composition and create a direct physical connection between the Jesus and the figures that surround him. I also opted to make use of the traditional halo surrounding Jesus’ head. Both symbols indicate spiritual light and power that is being symbolically transmitted to the other figures as it connects them to Jesus. The silhouette upon the cross at Jesus’ feet is not only his cross but the cross of all those who are suffering from oppression – yet continue to engage in the struggle for justice and equality.

From my perspective, the real question is not about Jesus, but “whose Jesus?” The Jesus of the oppressor never was and never can be the Jesus of the oppressed. The establishment has its own Jesus. He is not a person of color. He is not a Jew. He is not concerned with justice or equality and would never condone any kind of rebellion or insurrection. He is a wimp. His only interests are sentimental love and helping to maintain the status quo. Whose Jesus are you walking with?

My emphasis here is upon the person of Jesus as opposed to the risen Christ of faith. A Jesus who was born as a person of color into a minority community that was experiencing multiple forms of oppression. A Jesus who was: poor, stood up to a corrupt religious establishment, established his ministry by serving those who were considered the least within his community, was trapped by his enemies, abandoned by his inner circle, brutalized by the authorities, and ultimately tried and murdered by an oppressive government. This is the Jesus who has stood by my side, labored with me in my struggles and knows me in every aspect of my humanness. This is the Jesus with whom I identify. This is the God of the Oppressed!

To Purchase a Print click on the image above, or use the link below:

Damon Powell – Artist & Theologian

To purchase the original image please contact me directly at:

To join my mailing list click here: