Any examination of Black American history reminds us that the bible has always been a treasure trove of artistic inspiration within the Back community. Leslie King Hammond reminds us that “The narrative and moral parables of this sacred text provided…visual artists…with contextual and thematic strategies to artistically express their responses to the awesome and incongruous realities of the Africa-American experience.” One of the central themes in Black American theology-freedom has been a source of inspiration for Black American artists of every kind. It was the desire for freedom which inspired some of our nation’s most treasured forms of art, the Negro Spirituals.

A BLACK AMERICAN SPIRITUAL

Go Down Moses, Way down in Egyptland Tell old Pharaoh, “Let my people go”

When Israel was in Egyptland, “Let my people go” Oppressed so hard they could not stand, “Let my people go”

“Thus saith the Lord,” bold Moses said, “Let my People go: If not I’ll smite your first-born dead, “Let my people go”

“No more shall they in bondage toil, Let my people go, Let them come out with Egypt’s spoil, Let my people go”

The Lord told Moses what to do, “Let my people go” To lead the children of Israel through, “Let my people go”

Go down Moses, Way down in Egyptland, Tell old Pharaoh, “Let my people go”

This spiritual is a very poignant reminder of what I believe to be my task as a Black American artist and theologian. To speak whenever and wherever I can, to those who abuse their power in a manner which limits the freedom of others. With that thought in mind, part of my goal has been to attempt re-interpreting and re-creating biblical texts and themes into forms which are more reflective of modern life. This process must go beyond merely putting the same ideas and events into a contemporary setting, or simply depicting the characters with Negroid features (blackenizing) to the creation of new images and symbols which speak on their own terms.

In many ways. I am attempting to apply and illustrate theological and sermonic principles into the creation of my art. For me this process is primarily as one of prophetic proclamation using visual media. In my efforts to achieve this goal, I realize that my interpretations will always be filtered through my own being, personality, and experiences. I see this as an interpretive asset which helps to authenticate my vision.

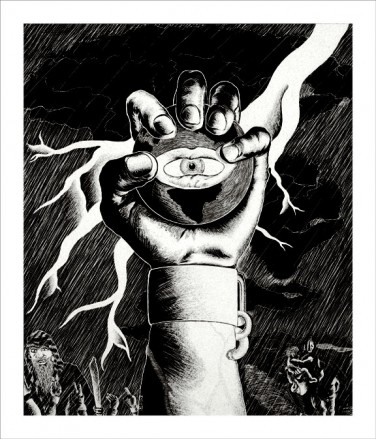

Keeping the above in mind, one of my main goals with this creation was to re-interpret the Exodus narrative holistically using graphic, symbolic, imagery which focused upon divine action, presence, and liberation.

SYMBOLISM

Most of the works which I encountered in my research seemed to focus upon either the person of Moses, or a single event within the Exodus narrative. These positions de-emphasized the role of God in the former, and kept me from grasping the significance of the event as whole in the latter.

The drama of the Exodus event is grounded in experience. It was a decisive event in Israelite history through which God revealed God’s self the liberator of an oppressed and downtrodden people. The primary agent within the event is God. God initiates the liberation narrative by identifying with the cries and suffering of the children of Israel, “And the people of Israel groaned under their bondage, and cried out for help…” (Exodus 2:23-25).

It is God who takes the initiative, God who reveals the divine self, and God who liberates the Hebrew community. Exodus 6:6 reads, “Say to the Israelites, ‘I am the Lord, and I will free you from the burdens of the Egyptians and deliver you with an outstretched arm and with mighty acts of judgment.” I felt this declaration was a key element within the Exodus drama overall. If we examine the narrative in its entirety this declaration becomes a very decisive element in how we must interpret everything else.

Not only does the role of God keep recurring within the narrative, but there is also an emphasis upon divine power and might. It is the might of a God whom is deeply immersed in the Hebrew community’s daily realities, and is not hesitant to be partisan, nor flinch from taking sides. The divine will and purpose are revealed by a divine disclosure of God’s goodwill toward the Hebrew community. This disclosure ultimately results in socio-political liberation through the destruction of the Egyptian oppressor’s military power. In other words, God takes the side of those who are oppressed (the Hebrews) and then initiates a series of events which ultimately dismantle the existing socio-politic, economic, and military power of the Egyptian nation (represented by Pharaoh).

Among the many images present within the narrative, I particularly found the imagery of the hand and out-stretched arm of God acting, intervening, and protecting the Israelite people to be particularly potent. This emphasis upon the arm and hands is repeated throughout the story. God makes Moses’ hand leprous, Moses tells Pharaoh that God has declared that he, “Let my people go…” which definitely connotes some type of hold or grip which Pharaoh has upon the Israelites. At one point, the mighty hand of God is outstretched toward Pharaoh. The outset of almost every mighty act Moses performs is initiated by stretching out his hand (with the staff), so that the hand of God may perform a mighty act for the people. It was from this constant reference, that I opted to use the hand and arm imagery as the primary symbol within this work.

The hand as a multi-functional symbol throughout the Exodus narrative. It can represent a variety of things on a variety of levels. It is the mighty outstretched hand of God which rises up to deliver. It is also the outstretched hand of the people crying out to God for liberation from their oppressor (lower right corner). It is the hand of Pharaoh raised in defiance of the divine imperative to free the Hebrews. It is representative of the hands of Moses and Aaron outstretched over the waters of the Red Sea. There are multiple meanings that can be derived from this image.

The shackled wrist represents the oppression of the Israelite people-but more importantly, God’s self-disclosure within the context of their liberation. God is the God for, and of the oppressed. “The God of the oppressed is a God of revolution who breaks the chains of slavery.” The shackled band signifies divine solidarity with the people while they are still within their state of oppression. God has declared that the Hebrews are to be set free. God has declared their liberation, and initiates actions which will make that declaration a reality by making use of political activity on their behalf (hence the broken shackles).

The orb represents the divine possession of the world as a whole, and the divine omniscient, omnipresent eye of God that not only sees and knows all, but continually speaks within the context of human history. That same God is still watching, and speaking to us now by calling each of us to aid in liberating those who are oppressed. The orb serves as a reminder of divine presence, control, and compassion for creation. When I think of divine compassion within the Exodus Theologian Elsa Tamez reminds me that “The oppression the Hebrews suffered in body extended as well to the innermost parts of their being. It touched their inner-selves, the transcendental part of their being, their dignity, their persons.” God is a compassionate being who relates to, and cares for all of creation in a every aspect of its existence.

The figure in the lower-right corner represents Moses. It is the prophetic figure of Moses who speaks on behalf of God in order to initiate the Hebrew people’s radical break from the social inequities which they were suffering in Egypt. Walter Breugermann points out that “…Moses dismantles the politics of oppression and exploitation by countering it with a politics of justice and compassion. The reality emerging out of the Exodus is not just a new religion or a new religious idea or a vision of freedom but the emergence of a new social community in history, a community that has historical body, that had to devise laws, patterns of governance and order, norms of right and wrong, and sanction accountability…Israel emerged not by Moses’ hand-although not without Moses’ hand-as a genuine alternative community.”

The figure of Moses serves as a reminder that God is still working in, and through the minds and hearts of ordinary people. Hopefully, God still speaks through us to proclaim the divine message of freedom and aide those who are in need. Below Moses’s figure, the people stretch their hands forth to God while at the same time seeking direction and guidance from the prophetic figure before them. Not only are their hands raised in defiance of oppression, but to also obtain direction and hear, “What thus saith the Lord.” The figure is representative of the eternal shepherd who must rise up, step forward and interpret the will of God with, and for the community.

The left-hand corner depicts the wilderness experience. It seemed unnecessary to depict a large group because the mass of figures would detract from a more pertinent point: despite the people’s liberation from Pharaoh, they still had to survive the wilderness. Even after liberation, they were still in constant need of divine guidance and direction. They were out in the open, alone, and vulnerable facing the harsh realities of the world (starvation, shelter from the elements, rest…), because of this they were still very dependent upon divine benevolence.

In a sense, each of us must face the world alone. We each must face the reality of the world’s vastness, and yet somehow find a sense of direction and purpose both physically, and spiritually. The wilderness is the place where we do this. The wilderness is the place where the Hebrews become a nation (Israel) as they cement their relationship to the divine by means of a covenant. I attempted to depict this journey through the use of a single figure traveling through a vast expanse. A single female figure represents the Hebrew community that will become the bride of Yahweh by means of the covenant. The power and presence of God is symbolized by the rain which is falling upon the figure. This rain is also symbolic of the harsh elements which can be encountered in the wilderness.

The elements which form the background operate on many levels. The rain falls steadily and equally throughout the composition. It is the permeating presence of God within the world both physically and spiritually. Just as water eventually permeates, covers, and touches everything; so does the divine presence. Thunder, lightning, and clouds are all a part of the experience of rainfall. In the bible, they are very symbolic representations of the divine presence and power. In the Exodus narrative, God speaks to the Israelites through a cloud, and is present with them in a cloud. Thunder is a symbol of God’s awesome power. The same power which was manifested to Pharaoh as he was forced to grant the Israelites their liberation. Thunder and lightning are part and parcel of the awesome display of divine power which accompanies the mighty hand of God.

To purchase prints click one of the link below:

Exodus is available in print format only.

SOURCES

Brueggermann, Walter. “The Alternative Community of Moses” in The Prophetic Imagination. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1978.

Cone, James H. God Of The Oppressed. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1975.

____________, A Black Theology of Liberation: Twentieth Anniversary Edition. New York: Orbis Books, 1986.

Cress Welsing, Francis. The Isis Papers: The Keys to the Colors. Chicago: Third World Press, 1991.

HarperCollins Study Bible New Revised Standard Version.

Hooks, Bell. Art On My Mind New York: New Press, distr. By W.W. Norton, 1995.

Moody, Linda A. Women Encounter God: Theology Across the Boundaries of Difference. New York: Orbis Books, 1996.

Studio Museum of Harlem, Challenge of Modernism: African American Artists 1925-1945. New York: Studio Museum of Harlem, 2003.

One comment